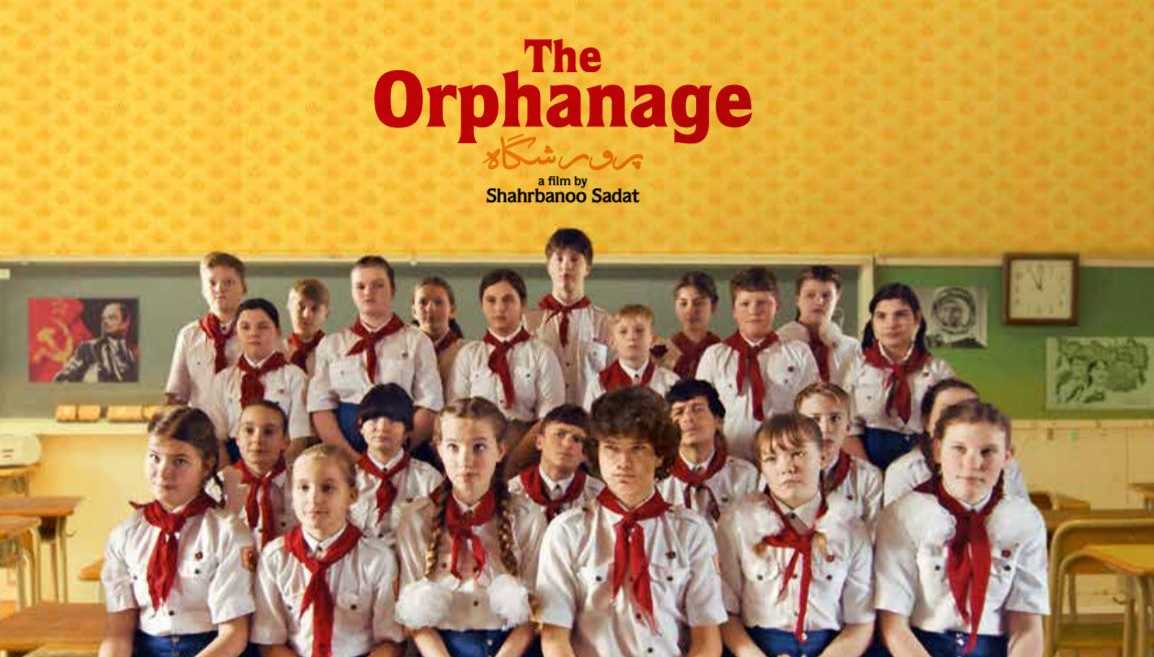

Interview mit ,,Kabul Kinderheim“ Regisseurin Shahrbanoo Sadat

AN INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR

The film is based on your friend Anwar’s memories. What elements in his story encouraged you to adapt them as a screenplay?

I found his story very honest, simple, and rich at the same time. His story took me on a journey through the history of Afghanistan over the last forty years. From the innocent point of view of an orphan. He was a child stuck in a war that was not his war. It’s exactly how I feel today living in Afghanistan.

To what extent did you try to stick to the true events? Did you use some elements of your own past to write the film?

Anwar spent 8 years of his life in the orphanage. In his autobiography, there are many pages full of characters, events, lots of history, lots of names of people and places, which only make sense for an Afghan audience. I read the pages over and over and I struggled a lot with myself to find the right balance between what happened and what actually should happen in the film. I wanted to make it easier to understand for an international audience, but I never forgot the Afghan audience. I made the time period shorter, even though the story starts in 1989 and ends with Mujahideen taking over Kabul in 1992, but I kept the time fictional so characters don’t grow up, but one still feels that time has passed. I also cut down the number of characters. Sometimes I mixed different stories and characters to make them my own. The Bollywood film songs are the big part I added to Anwar’s story, but Anwar was really a huge fan of Bollywood and sold cinema tickets on the black market.

Is your friend’s testimony an indirect way of questioning Afghanistan’s recent history?

One can’t question the present if one doesn’t know the past. There are enough films about Afghanistan today and I swear the whole world knows there is a conflict there. What interests me is to dig into the past, to find out where all this mess actually started from.

You use a lot of cinematic “grammar” from Bollywood in the film. How did you come up with the idea of creating your own Bollywood sequences?

Well, Bollywood is a huge film industry in my part of the world, and the friendship between Afghanistan and India has made it even stronger. Almost all Afghans can speak Urdu because they watch so many Indian movies. Perhaps the 1980s were the golden time for that because we had cinema theaters and there was peace, at least in Kabul, the capital.

In Afghanistan today, there are many “Z films” being produced one after another, influenced by Bollywood movies. So, the idea was not very far away from me. Also, the fact that Anwar sold cinema tickets on the black market and was a big fan of Bollywood made this idea fit into the film.

The passionate reaction of the audience while watching an actual Bollywood at the beginning of the film is incredible. What was the significance of the Bollywood culture in Afghanistan during the 1980s? Has it changed nowadays?

Afghans are not expressive people, but they love Bollywood, where they get the emotion and drama. I love this contrast. Maybe that’s why the love for Bollywood has remained the same. It is their only way of expressing themselves. The only difference is the time. The 1980s were the golden time, because of the existence of cinema theaters all over Kabul. Now people watch movies on the internet or buy DVDs on the black market. What Bollywood offers fascinates people. Dreaming, living a perfect life that is not possible in reality, friendship, love, and joy. These are things people badly miss in their real life, especially when living in a war-stricken country like Afghanistan, where there are hardly any basic rights. In my head, it makes sense where this interest comes from.

The orphans in the film come from very different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Did you want the orphanage to be representative of the diversity of Afghanistan?

The orphanage is one of the few places in the entire country where everyone lives together, no matter of religion or ethnicity. I was interested in this fact, especially when in the early 1990s the ethnic civil war in Kabul started, and many killed each other only because they didn’t belong to the same ethnicity.

Could you tell us more about the production of the film? What were the difficulties you encountered during the production process?

I shot the film in Tajikistan, one of the post-soviet countries in Central Asia, the northern neighbor of Afghanistan, where places look similar to Afghanistan. I cast non-professional actors from Afghanistan and flew them over to Tajikistan. Getting passports and visas for the actors is always very difficult. Tajikistan denied issuing us the visas, and we had to apply a second time.

We received regional funding from Germany and Denmark to shoot the Bollywood scenes in Russia there, but getting a Schengen visa is impossible for Afghans. There is no embassy in Kabul that issues visas anymore, so in order to get a Schengen visa, we had to travel to Pakistan and in order to travel to Pakistan, we needed visas for Pakistan. Getting visas for Pakistan is also tricky as they issue visas depending on their mood and depending on the current political situation between the two countries. The Danish embassy denied our visas the first time and we couldn’t continue shooting and had to make a pause of 4 months between the shootings in Tajikistan and Europe to get the visas for our main cast.

The other big challenge is that I feel alone when it comes to creating Afghanistan in another country. There was no art director involved in the project, and Anwar and I collected every single piece of props and costume by ourselves. Later we got some help, but still, we made an entire Tajik brothel into an orphanage with a group of construction workers, who I worked together with before on my previous film Wolf and Sheep. There where we made an entire Afghan village.

Could you tell us more about the film production in Afghanistan? How do you think that film-directing can be encouraged there?

There are many production companies registered and many filmmakers making films, from Z movies to short films and documentaries, also a few fiction feature films. I think the move is very slow but there is one. We need time to create our own cinema language. I think Afghan filmmakers are confused and lost between what they want to tell and what they think the world expects them to tell. I hope one day we can be the storytellers of our stories. It’s totally fine with me that international filmmakers are attracted to Afghanistan, but what is shown from Afghanistan is very cliché and shallow and miles away from the reality there. My wish is one day in the very soon future. Afghan filmmakers dare to share their stories in the way they want to tell them.

You cast some of the same young unprofessional actors as in your first feature, Wolf & Sheep. You saw them growing up. What kind of relationship have you developed with them?

I was surprised when I worked with Qodrat for the second time on the set. I realized he is older now and the way I worked with him on Wolf and sheep doesn’t work anymore. This time, our relationship was more professional; I trusted him and talked to him about the scenes more in details. I found him intelligent and very patient.

Alongside its historic background, the film also deals with the coming-of-age of the different orphans. Was this part entirely written or did you let the comedians improvise?

Everything was written. Even though they improvised a lot, in the end, it is very similar to what I wrote.

The film’s conclusion remains open, with a spectacular dreamlike approach. Why did you choose to end it this way?

That’s an easy answer! I wanted to let the children win! We all know what happens in war. Women, children, and civilians get killed and lose. I didn’t see a point in repeating this one more time, while I actually had the power to rewrite it.

Qodrat loves to imagine himself as a film character. Were you like him as a teenager? What role did cinema play for you when you were growing up?

I like Qodrat. He is smart and I think he can make a career for himself one day as an actor. Cinema came into my life very late. I stepped into a real cinema theatre for the first time when I was 20. I had a different childhood.

You originally planned to direct five films inspired by your friend’s story. Is it still a current project? Or do you have other directing aspirations?

Part one (Wolf and Sheep) and part two (The Orphanage) are done. I’m working on the third and fourth parts now. All these stories are inspired by Anwar’s piece. He tries to publish his diary and inside of me, there is a wish growing to make a film not based and not inspired by his work. I’ll do it one day, when I am older, perhaps when I finish this pentalogy.